Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:15

Pushkin. Today's

0:21

show includes, among other things,

0:24

directed evolution, rabbit poop,

0:26

sustainable aviation fuel, and

0:29

polyester. Let's

0:31

do It. I'm

0:37

Jacob Goldstein and this is What's Your Problem,

0:40

the show where I talk to people who are trying

0:42

to make technological progress. My

0:44

guest today is Jennifer Holmgren, the

0:46

CEO of lonz Tech. Jennifer's

0:49

problem is this, how do you take pollution

0:52

from steel plants, smokestacks,

0:54

beat it to bacteria and get

0:56

the bacteria to excrete Ethanol.

1:01

Ethanol is a kind of alcohol. It's the kind

1:03

of alcohol you drink, and in addition

1:05

to being made in the alcohol you drink,

1:08

ethanol is made as a fuel additive.

1:11

In that context, it's often made from corn

1:13

or sugarcane. But expanding

1:16

the footprint of industrial agriculture

1:18

to grow, say more corn for fuel,

1:21

can mean more emissions and

1:23

higher food prices. Hence the

1:26

idea behind lonz tech find

1:28

a different source of ethanol, one

1:30

that doesn't require food crops. Lonza

1:33

Tech was founded in two thousand and five by

1:35

two scientists from New Zealand. Jennifer

1:38

Holmgren was not one of them. She

1:40

joined the company as CEO in twenty

1:43

ten, when Lonzo Tech was moving from a

1:45

sort of proof of concept to scaling

1:47

in the real world. We started our

1:49

conversation by talking about the scientific

1:52

work that led to the company's creation.

1:56

So is it right that

1:58

the first kind of insight

2:00

or idea is that

2:02

there is a bacteria that ideally,

2:05

theoretically could turn pollution

2:07

carbon monoxide into ethanol.

2:11

That's right. And the founders

2:13

knew that this was possible because

2:15

they knew that they were gas eating organisms,

2:18

and they were able to go to a library in Germany

2:21

which stores organisms that are known and

2:23

cataloged and say I want that one, and that one

2:25

and that one, and bring it to their

2:27

lab and start using it.

2:29

So they were getting like vials of bacteria.

2:32

Yeah, yeah, huh yeah, absolutely.

2:35

And did they find one that worked.

2:37

Absolutely. But they had to do a lot of

2:39

optimization because it's a bacteria

2:42

that wants to make a different molecule, acetate,

2:45

and they wanted to make ethanol, and

2:47

so they had to do a lot of work to optimize

2:49

the bacteria. And they did it without using

2:52

genetic methods. They did it all

2:54

by directed evolution, kind of like you

2:56

you know, put two orkids together to make a third,

2:58

So let's.

2:59

Let's talk about that a little bit. So what what

3:01

was the bacteria that they found.

3:04

It's called C. Auto. So

3:07

the long name is C. Auto orhanogenum,

3:10

and we call it seouto, and

3:13

it is an anaerobe. You

3:16

can only find it in places where

3:18

there's no oxygen, but it was around

3:20

at the beginning of the Earth

3:23

when there was no oxygen.

3:27

Glory days exactly.

3:28

It's glory days. We like to say, it's

3:30

our great great great great great grandfather.

3:33

Yeah, where does it hide? Where does

3:35

a where does a microbe that doesn't like oxygen

3:37

hide? Today?

3:38

Well, it's been found in you

3:41

know, gut biome like from

3:44

rabbits. It's been found in.

3:48

Is it true that it's in rabbit poop?

3:50

Well? Yeah, so I was trying to be

3:52

more delicate and saying bottom,

3:56

yeah, take rabbit poop. Yeah, it's found

3:58

in rabbit poop. So for all

4:00

we know, it could be in our guts too. I don't know,

4:02

but it's definitely in rabbit pooh.

4:05

It is in you can find

4:07

it in vents, underwaters, you

4:09

can find it in all of these places where

4:12

and it's that's actually one of the

4:14

neat things about this bacteria. It

4:16

is robust, it's strong,

4:19

and it doesn't like oxygen, so oxygen

4:22

will kill it. But it is something

4:24

that allows you to do industrial biotech.

4:27

Huh. So they find this

4:30

very ancient bacteria. It's

4:32

robust, but it's not it's

4:35

not evolved to make ethanol.

4:38

It's not evolved to make what you want. What's it evolved

4:40

to make?

4:41

It makes acitate as a primary

4:43

product. So yeah, they evolved

4:46

it to make ethanol as the primary

4:48

product.

4:48

So there is this sort of field of directed

4:51

evolution, right, that is

4:53

that that they're using here to like tell me about directed

4:56

evolution. That's a relatively young

4:58

field in this context, right, What is it? What does it

5:00

mean? How do you do it?

5:02

Well, it means you're

5:04

putting stress on the bacteria

5:07

and select colonies

5:10

that are making what you wanted to make, and

5:12

if you wanted to make ethanol, you

5:14

select for those.

5:15

So eventually, through sort of applying

5:18

selective pressure in this way, they

5:20

get to a strain of c auto

5:23

that loves to make

5:25

ethanol.

5:26

Yep.

5:27

Okay, yep. And that's around

5:29

the time you get to the company, Is that

5:31

right?

5:32

Yeah, So there was still

5:34

optimization to be done, and they had started

5:36

using doing a pilot at a steel

5:38

mill in New Zealand, and so

5:41

I knew the system worked. I just didn't

5:43

know how scalable it was to

5:46

commercial scale. And by scalable

5:49

I don't mean that you couldn't build a big one, but that

5:51

you could make money for me building a big

5:53

one.

5:53

That's such a huge issue,

5:56

right, Like this idea of people call it

5:58

technoeconomics. Like there are

6:01

a million clever ideas

6:03

like this that are elegant and intellectually

6:05

satisfying. But in this big

6:08

sort of commodity, global

6:11

scale world, the question is like, great,

6:13

but can you make it at a competitive

6:15

price at scale? Right? So

6:19

how do you start to answer that question?

6:22

Well, I think you need to start

6:24

with what you think you can do, and

6:27

then you validate it as you go from lab

6:29

to pilot to demo, and then you ask

6:31

yourself what else do I need to do to make it

6:34

economic? And in our case,

6:37

it's a really great bioreactor.

6:40

It's also water recycling

6:42

and media. If you don't you

6:45

know, let me explain media. So when

6:48

you grow a plant, you need fertilizer, right,

6:50

nitrogen sulfur. And

6:53

so what we had to do was figure

6:55

out how to feed at a minimum amount of

6:57

nitrogen and sulfur envitnments. All

6:59

of these little things energy use,

7:02

All of these impact the cost

7:04

and so in a lot of ways, I

7:07

like to think of a technoeconomic analysis as

7:09

a tool that allows you to say,

7:11

I got to optimize that because it's

7:13

too expensive.

7:15

So now you have factories in countries

7:17

around the world. You were

7:19

to some degree at least operating at scale.

7:22

I'm curious, what are a few things you

7:24

had to learn to get here?

7:27

Well, I think a specific one is finding the right

7:29

partners. We ended up going

7:31

to China because we were looking

7:33

for a steel mill that we could work with, and

7:35

fifty percent of the world steel was made in China.

7:38

They were also in growth mode. They

7:40

wanted to reduce their carbon intensity, but

7:42

they wanted to use

7:45

it as a license to grow. And

7:47

so China was in the right

7:49

mode to think about new technologies,

7:51

and so we were able to go there find

7:54

a partner who was interested in using our technology

7:57

and then demonstrating it. We built

7:59

one hundred thousand gallon a year

8:01

facility, and then we use

8:04

that as a path to building basically

8:07

a fifteen million gallon a year of facilacility,

8:09

and that's what we have operating now.

8:13

We have six facilities, average

8:16

size thirty to fifty million gallons

8:19

a year.

8:20

Meaning each one produces thirty to

8:22

fifty million gallons of ethanol. So

8:27

tell me about a couple of the things you learned going

8:29

from you know, the lab

8:31

to tens of millions of gallons a year,

8:33

Like, what were a couple of things that didn't work the

8:35

first time that you had to figure out sort of

8:37

specifically.

8:39

You know, the bacteria's robust, like I

8:42

told you, but it also needs

8:44

to be coddled a little bit sometimes,

8:46

and so you need to install

8:48

some type of pre treatment, and

8:51

so learning how to pre treat

8:53

cheaply it was very important. Learning

8:56

when we went from doing a steel milk

8:58

gas to a fair alloy gas to a

9:00

gas that's made from municipal

9:03

solid waste right from trash. You

9:05

you kind of handle the gas a little

9:08

bit differently. And so we

9:10

had focused on our process and

9:12

we had spent some time on the gas,

9:14

but we really learned, you know what, spend

9:17

a little more time on the gas. So that's

9:19

one thing we learn. The second

9:21

thing I think we learned, and something

9:23

that's obvious right, Building

9:26

good relationships matters, right. Nothing

9:28

works the first time, and having partners

9:31

that are willing to be on the journey to improve

9:34

and optimize as you scale is important.

9:36

Right. These units are not like

9:38

a Christmas gift. You open the box and voila,

9:41

we're running a capacity. And

9:44

so really it's about your partners

9:46

and about their commitment to you,

9:49

to the technology and to getting to scale.

9:54

Let's talk about just what it looks like. So you said

9:56

you have how many how many

9:58

operating six are their China

10:00

and India and Europe.

10:02

We have one in Europe as well in Ghent in

10:04

Belgium with our solar middle.

10:08

So in a somewhat

10:10

abstracted way, just like basically, what does one

10:13

of your facilities look like?

10:14

Like?

10:14

Maybe we should start at the at the

10:16

smoke stack, right, So there is what

10:19

used to be pollution coming out a smoke

10:22

stack or what happens.

10:23

You don't let it go out, You intercept

10:25

it before it goes out, You compress

10:28

it and you put it into a reactor.

10:30

So there's a gas and you particularly you

10:32

want carbon monoxide. Still is that your.

10:35

Put you want carbon monoxide? You

10:37

can also use carbon dioxide if you have

10:39

hydrogen. It depends

10:41

on whether you have hydrogen or not how well you can

10:44

process carbon dioxide. So let's just focus

10:46

on carbon monoxide. That's like sugar

10:48

for our bacteria. It's like yum,

10:50

I'll take that.

10:51

So then is the first thing you have to do? Separate

10:54

out the carbon monoxide from the rest

10:56

of the gas.

10:57

You don't, Okay, So if you have

11:00

a carbon monoxide, say forty percent

11:02

carbon monoxide stream in a bunch of

11:04

other gases, you can just pump

11:06

that into your bioreactor and the bacteria

11:08

will find it carbon monoxide and you'll

11:10

just ignore all the other molecules floating around.

11:12

Okay, So you pump that into the bioreactor.

11:14

What's it what's it look like inside the biorector?

11:17

What's going on in there?

11:18

Yeah, so imagine a bunch of bubbles

11:20

and imagine you've got bacteria

11:22

that are dividing. Right, they're alive, they're dividing.

11:25

So it's kind of not

11:27

a clear liquid. You're you're seeing

11:30

what look like little grape particles in

11:32

there, but it's just bacteria floating

11:34

about. Gas bubbles come in.

11:37

That's all you see. And then

11:40

on the back end you see ethanol.

11:42

And in the bubbles in the tank. Is

11:44

that like a medium you have created

11:47

that your bacteria likes to

11:49

live in.

11:49

That's that's right, that's right. They're getting

11:51

their vitamins, they're getting their minerals, they're

11:53

getting their carbon source, that carbon

11:55

monoxide, and they're floating about

11:58

enjoying their day.

12:00

And you're bubbling in the carbon monoxide the

12:02

way like if there's a fish tank, you just bubble

12:04

in the.

12:04

Air exactly now. It

12:08

it's continued. The process

12:10

is constantly and the water is constantly

12:12

moving around, and so it's

12:14

not quite like a fish tank. But

12:16

it's a great analogy and that works

12:18

really well. And the key

12:21

you said the bubbles like a fish tank. The

12:23

key is to make those bubbles as small as possible.

12:27

So it's kind of faking out a

12:29

dissolution, right, It's like they're

12:31

dissolved the amount of dissolved carbon

12:33

monoxide getting to the bacteria

12:36

so that they can find it, eat it and

12:38

poop out ethanol.

12:40

And how does the ethanol sort of come out

12:42

of the tank.

12:44

The ethanol is with water, and

12:46

so we have to distill the ethanol

12:49

out and then we take the

12:51

water which also has media and other

12:53

things and pump it back into the reactors

12:56

so that we're not wasting anything. We're

12:59

you know, we're separating the bacteria, putting

13:01

it back in the reactor, separating the ethanol

13:03

through distillation, and then you just

13:05

take the ethanol and clean it as much as you want.

13:09

For fuel grade to blend with gasoline

13:11

doesn't need to be that clean. For

13:14

putting it into cosmetics,

13:16

it needs to be really clean.

13:19

And who

13:21

are you selling your ethanol to, So.

13:24

Most of the ethanol goes into blending with gasoline.

13:27

That's what our partner in China is doing.

13:31

But what we do is we take a small

13:33

amount of it right now and we've used it to

13:35

do project development or brand

13:38

development. So Cody, for example,

13:40

uses our ethanol in some of their perfumes.

13:43

We've also converted it to polyester, and

13:46

On has made running apparel

13:48

with the polyester made from these recycled

13:51

emissions. Mebel has

13:53

used it in cleaning products. So we have quite

13:56

a few partners that you would

13:58

recognize, H and M. Craghoppers,

14:00

they've all used our polyester. And it's

14:03

kind of neat, right because if you stop

14:05

and for a second think about this, you

14:08

say, you know this was going to be pollution,

14:10

it was going to be greenhouse gases and particulates

14:13

and instead I'm wearing it.

14:16

Yes, and how's the price.

14:19

So it's more expensive than conventional

14:21

polyesters. It's you

14:25

would say, it's anywhere between one hundred

14:27

and fifty twoe hundred and seventy

14:30

percent. Fortunately,

14:32

we have partners who are willing to pay

14:34

more in the raw materials because the

14:37

raw material is not what impacts

14:39

the price of the product.

14:41

Right, they can pay They can pay

14:43

significantly more for the polyester, and

14:46

it's such a trivial percentage of the final

14:49

cost of the good that it doesn't move the needle much.

14:51

Well, you know, I would have thought exactly

14:54

the way you just said it. But

14:56

unfortunately what it does is it impacts

14:58

their margins. And in a world that's obsessed

15:00

with profit and margins, you

15:03

have to give credit to our partners for being able

15:05

to say I am going to make an

15:08

investment in creating this right

15:11

because their business leaders

15:13

are not getting the margins that others

15:16

are getting. And so I

15:20

think this is something I want to really hash

15:23

out because I think we're driven to reduce

15:25

our costs and to increase our profit and

15:28

we've got these brave souls who are saying,

15:30

well, I got to reduce carbon too, and

15:33

that's important to us and to our future.

15:35

And I'm going to go against the trend, and

15:37

I'm not going to reduce my costs or

15:39

increase my profit. I am going to do something

15:42

good. So ARII Craghoppers

15:44

has a whole line of clothing with our stuff,

15:47

and they're trying to

15:49

help us get to

15:51

a scale where we can reduce the costs

15:54

so that maybe someday they'll get to

15:56

the margins they need.

15:58

Yeah, I mean, I feel like, I

16:01

feel like it's great that these companies want

16:03

to do this. But to be meaningful

16:05

at a global level, you

16:07

need to get to a place where the ethanol

16:09

you sell is the same price

16:12

as other ethanol, right, And

16:16

I'm curious what has to happen for you

16:18

to get there? Well, first of all, is that right?

16:20

Do you think of it the same way? Are you trying to get to a

16:22

place where your

16:25

ethanol has cost the same as corn

16:27

ethanol or any other ethanol?

16:29

Right now, it's actually pretty close

16:31

to corn ethanol. It's just that it costs a lot

16:33

more than ethylene, which is how polyesters

16:35

made.

16:36

I see, So for fuel. Is

16:38

the ethanol you make price competitive?

16:40

It is pretty equivalent. Yeah. Yeah,

16:42

the capital installed cost is much

16:44

higher because they've optimized their

16:47

capital for years and well hundreds

16:49

of years, whereas we have not. But

16:52

once you get past the capital recovery piece,

16:54

the costs are about the same.

16:56

So you're saying you're like competing against sort of

16:58

depreciated assets. They built factories a long

17:00

time ago. They don't sort of have to pay for the

17:02

factories every month the way

17:05

you do that kind of thing, that kind of challenge.

17:07

That's right, that's right, But

17:10

we'll get there. But you ask the more

17:12

important question, and I guess we're

17:16

focused on keeping carbon in the ground. At the end

17:18

of the day, this lineary economy is not going

17:20

to work, and we need

17:23

to find a way to reuse all carbon

17:25

that's already in circulation in our system,

17:27

whether it's municipal solid waste, whether it's

17:29

industrial waste, whether it's CO two that's in

17:31

the atmosphere. We've got to figure out

17:33

how to use that as the resource

17:36

from which everything is made. So it's

17:39

great, we need to reduce consumption, don't

17:41

get me wrong, but we have a whole lot of global

17:43

economies that are growing, and so how

17:46

do we deliver to them what

17:48

they need without

17:51

pulling more carbon out of the ground. And

17:53

that is what we focus on. So the

17:55

question is are you cost competitive? Well,

17:57

there's a lot of things that we can do that make us cost

17:59

competitive when we get the bigger

18:02

scales and we deploy more units. You

18:04

know, this is the beginning of the journey, right the early

18:07

days of the cell phone versus now. And

18:09

so what you've got to do is just build more

18:11

and reduce costs, improve the technology,

18:13

reduce costs. But the other thing that

18:16

biology allows you to do is

18:18

it allows you to skip steps that you

18:20

would naturally use in the petrochemical

18:22

world. So today

18:25

to make polyester, I go

18:27

from ethanol to ethylene to ethylene

18:29

oxide to meg to

18:32

polyester. Now what if

18:34

I could go from the gas not

18:36

to ethanol, but to meg. Now

18:39

I've put that whole supply chain inside

18:41

my bacteria. Now

18:44

I can be competitive because I'm

18:46

processing less and I'm doing

18:48

it at room close to room

18:50

temperature, not like a thermo

18:52

catalytic process. So there is

18:55

a day when I believe we'll be competitive, but

18:57

I think we're always

18:59

going to have to ask ourselves the question what

19:01

are the externalities that go along

19:03

with the costs of the things we buy? And

19:05

I know that's a delusional question. Everybody's

19:08

like, well, we'll just take not all of those

19:10

and get a lot of keep stuff made from fossil

19:12

carbon. But are we

19:14

going to carbon tax? Do I have

19:16

to be competitive with fossil.

19:19

Well, like a carbon tax would solve the

19:21

externality problem, right. The problem

19:23

is when people use fossil

19:25

fuel, they pollute, and they impose a cost on the

19:27

world, and that cost is not reflected in the price

19:29

of the good, and that is a market failure

19:32

and you are competing against that market failure.

19:34

And I agree that a carbon tax is

19:36

a good idea, it's hasn't

19:39

taken off politically in

19:41

a broad way. So that's

19:43

a challenge, right, And like people being

19:45

willing to pay a green premium, seems limited

19:49

by human nature at some margin.

19:53

And that's why I want you to applaud the people

19:55

that are trying fair enough.

19:59

In a minute, how Lonza Tech is working

20:02

on developing sustainable jet

20:04

fuel. Airplane

20:18

emissions are a really hard problem

20:20

to solve. The physics of flight

20:22

make it hard to create an economically sound

20:24

electric plane, although people are

20:26

working on that. People are working on hydrogen

20:29

powered planes, but that's also really

20:31

hard. It's clearly going to take a long time.

20:34

So in the short to medium term

20:36

progress is more likely to come

20:38

from what are known as drop

20:41

in sustainable aviation fuels,

20:44

as in you can just drop them

20:47

into the currently used fuels without

20:49

having to redesign the whole plane. And

20:51

Jennifer Holmgren has been working on drop

20:54

in sustainable fuels since before

20:56

she came to Lunza Tech.

20:58

I've been working on sustainable aviation fuel

21:01

from before there was such a thing as a drop

21:03

in sustainable aviation fuel. So I

21:06

worked on the first drop in fuels

21:08

in my old job. We did flight demos,

21:10

flight of the Green Hornet, all of that. We showed

21:13

that you could make a hydrocarbon right

21:16

and biofuels until then were

21:18

oxygenates, ethanol, biodiesel,

21:21

So we showed we could make a hydrocarbon

21:23

that looked exactly like jet fuel,

21:25

and that was certified. Those are the first

21:28

drops that were certified for sustainable

21:30

aviation fuel. All of

21:32

the fuel that's made today that

21:34

goes into an airplane that is

21:37

not made from fossil

21:39

carbon is made with that type of

21:41

a process that takes fats,

21:43

oils, greases and makes

21:45

them to sustainable aviation fuel. The

21:48

problem with that is how much

21:51

we go back to the same problem we started

21:53

with. How much of these biological

21:55

feedstocks are there? The world uses

21:57

one hundred billion gallons

22:00

of aviation fuel today.

22:03

You can't do it just food. And

22:06

so when I came to lands Attack, I wanted

22:08

to develop a route to aviation fuel

22:11

from all of this ethanol that you could make

22:13

from all of these waste resources. And

22:16

that's why we were Pacific Northwest National

22:18

Lab to develop a route to take

22:20

ethanol. Any kind of ethanol doesn't have to be ours.

22:22

Lots of other people know how to make ethanol to

22:25

make sustainable aviation fuel.

22:28

When we got that certified for

22:30

flight, we did the ASDM work. We

22:32

flew a flight with Virgin Atlantic from

22:34

Orlando to Gatwick commercial flight

22:37

by the way, that was kind of cool, two hundred plus

22:39

people on board, made

22:42

from recycled steel mill emissions.

22:46

We realized that what we needed to do was build

22:48

a ten million gallon a year facility,

22:51

a large commercial scale, mini

22:53

commercial scale facility, and

22:55

so what we decided to do is to

22:59

launch land SUGGETI zone entity

23:01

and raise cash into it so

23:03

that we could build that plant and go really

23:06

really fast. And so

23:08

that plant is in Georgia and

23:11

it's in Soaprodue, Georgia, and it should

23:13

be starting up momentarily.

23:15

I would say more like tomorrow.

23:18

What does momentarily mean.

23:19

And think of it in it's

23:22

in the last stages of shakedown, say

23:24

within the next couple of months kind of differing.

23:27

And what's going to happen at that factory.

23:30

We're going to take ethanol and we're going to contain

23:32

convert it to sustainable aviation fuel

23:35

using the lens of jet alcohol,

23:38

ethanol to sustainable aviation

23:40

fuel, alcohol to jet technology.

23:42

And is that fuel like a supplement?

23:45

Like how does that work?

23:46

Right now? Certification is for fifty

23:49

to fifty blends. You can only put

23:51

it with kerosene fifty to fifty.

23:56

And are you using the

23:58

ethanol you make from

24:01

pollution from waste emissions at

24:03

that plant?

24:04

No, Because we decided that

24:07

since what we needed to prove at commercial

24:09

scale was the sustainable

24:11

aviation field technology, we could

24:13

use any ethanol to do that. We didn't need to raise

24:16

the capital to build both. And

24:19

so right now it can use our ethanol

24:22

made from waste emissions, or it can use

24:25

sugar cane ethanol, corn ethanol,

24:27

cellulos any ethanol that they can

24:29

find. That's the first

24:32

part of the journey is just to show that they

24:34

can get that technology to commercial

24:36

scale.

24:38

And what ethanol In fact, what is

24:40

the source of the ethanol you're going to use there?

24:42

The first ethanol will be sugarcane ethanol

24:45

that's been brought from Brazil.

24:47

And so what is the broader context

24:49

for sustainable jet fuel right now? Like

24:51

I know that's the whole conversation. Planes

24:54

are very hard to decarbonize in many

24:56

ways, So give me the broader

24:58

context for jet

25:00

fuel and where your plant fits.

25:05

Well, you know, the world

25:07

uses one hundred billion gallons a year

25:10

of aviation fuel. The

25:12

target that the industry has set for itself

25:15

is a minimum of ten billion

25:17

gallons by twenty thirty

25:20

of sustainable aviation fuel. And

25:22

today we're in the hundreds.

25:25

It's let's say one hundred million

25:28

gallons.

25:28

Okay, So it has to go up

25:31

by a factor of one hundred in

25:33

a few years if they're going to make that. And

25:36

just just like really dumb

25:38

question, like what makes sustainable aviation

25:41

fuel sustainable, Like what does

25:43

it mean to say sustainable aviation

25:45

fuel? Like what is that?

25:47

It just means it has a lower carbon footprint,

25:50

but it doesn't do it at the cost of a very large

25:52

water footprint or other things. Right, So the

25:54

full life cycle analysis, the

25:57

focus those in greenhouse

25:59

gas emissions and a reduction in greenhouse

26:01

gas emissions.

26:03

And is the basic idea that ethanol

26:06

has lower greenhouse gas

26:08

emissions? That and oil

26:11

as a source for jet fuel And is that

26:13

the very basic idea?

26:14

Yeah, So the basic idea is take the ethanol

26:16

to aviation fuel and compare

26:19

that to fossil

26:21

derived petroleum derive aviation

26:23

fuel. That's where you make the comparison,

26:25

not at the petroleum. That's

26:27

a hard comparison to make. You make it at the

26:29

product what you're going to put on the plane.

26:32

And so just tell me more about

26:35

you know, you're building a sustainable jet

26:37

fuel plant, Like what

26:40

is the broader industry? Like are there

26:42

different technologies at your plant?

26:44

Like what, I don't know anything about that side of the business.

26:46

Tell me something about it.

26:48

You know, you need to imagine a refinery,

26:50

right, that's exactly what this looks

26:53

like. If you drive by our plant

26:54

in Soupertin, you

26:57

it'll be like you're looking at a refinery,

27:00

a refinery that is small,

27:02

because refineries actually

27:05

take very dense liquid

27:07

and convert it to a bunch of different products through

27:09

a bunch of unit operations. We only have

27:11

really compact unit operation. It's

27:13

really three steps. Takes the ethanol to

27:16

ethylene, think of that, then

27:18

take ethylene to

27:21

sustainable aviation fuel in a two

27:23

step process. The ethanol to ethylene

27:26

is done with our partner technique. They

27:28

have a technology that efficiently takes

27:30

ethanol to ethylene and

27:32

then we go from.

27:33

There and is

27:35

the hope that you will use

27:39

your Lonza tech ethanol

27:42

as the input at this plant

27:45

soon eventually.

27:47

Sure, we will

27:49

use it at this plant. But also one of the things

27:52

we're doing is building plants together. We have projects

27:54

across the world in Europe, in

27:56

the Middle East where we're taking waste like

27:59

municipal solid waste, taking it

28:01

to ethanol and taking ethanol to saffaf

28:03

is sustainable aviation. Yes, thank you for that.

28:06

Yeah.

28:06

Yeah.

28:06

And we call that circular air

28:09

by the way, that joint offering

28:11

because obviously it's circular

28:13

carbon from waste to

28:16

aviation fuel, and it's the joint lens

28:18

of tech lansa jet. So we do expect

28:20

this plant, to expect other plants to use

28:23

our ethanol, but moreover, we expect

28:25

integrated solutions.

28:30

I feel like there's this long

28:34

history of people trying

28:37

to use synthetic

28:40

biology biotechnology to make

28:42

fuel, and it has been really hard for

28:44

a long time, and people talk about why

28:47

it used to be a bad idea or why people who

28:49

aren't making fuel talk about why fuel

28:51

is not the right thing to make, Like, tell

28:53

me about that history.

28:56

I mean, look,

29:00

you're trying to do something that's been

29:03

done in a specific way for over one hundred

29:05

and twenty years, right, and so

29:07

now you're going to say, well, I'm going to do it in new

29:09

way and oh, by the way, it's going to be cheaper,

29:11

cleaner, and better. And it's like, okay,

29:14

let's get a dose of realism here. When

29:19

you look at sustainable aviation fuel.

29:22

I believe that the use of fat, soils

29:25

and lipids, which is what is being done

29:27

today. We're seeing more and

29:29

more plants being built, so you're

29:31

starting to get to the Okay, this is the cheaper

29:33

part of the curve. Just like we did

29:35

with solar, just like we did with cell phones.

29:38

The only problem is now you've got to get to a

29:40

point where you're going to be feedstock limited. And

29:42

we just have to do the same thing with our technology

29:44

and other technologies that are out there. Build

29:47

enough, get to capacity, reduce

29:49

costs, and keep building. And

29:51

I think most people don't think about technology

29:54

that way. Is sort of expected

29:56

magically to show up without remembering.

30:00

I always used to laugh, you know, I remember in

30:02

twenty ten, because I have these

30:04

articles. You'd see all

30:06

of these publications. You

30:09

know, solar is ten years

30:11

out and will always be ten years out. Those

30:13

were literally the headlines, right, you're

30:15

nodding, so I know you remember this. But

30:18

here we are. You can't turn around without

30:20

seeing a solar installation, and every day

30:22

we make it cheaper and better. It's cost

30:24

competitive with fossil carbon power.

30:27

And I just think people need

30:29

to realize new technologies

30:32

take twenty thirty plus years to deploy

30:35

in a way that makes sense, and our technology

30:38

is completely disruptive. Nobody

30:40

had ever done this gas fermentation before,

30:43

so I think a thirty year cycle to get

30:45

to where you're economically viable and

30:48

competitive everywhere is not

30:50

unreasonable. We've been around for twenty years.

30:52

We know our technology works. We derisk

30:55

the technology, we've deristd the market. But

30:58

now instead of deploying five at a time,

31:00

we want to desploy twenty at a time. So

31:02

you got to reduce the costs.

31:06

What what do you think

31:08

might go wrong? Like, what would

31:11

be reasons you might not make it

31:13

to where you want to get to.

31:18

Yeah, that's a lovely question.

31:22

The hurdles are big, right, you

31:25

know, legislation stands against you. Nobody'd

31:29

ever heard of us doing

31:31

gas fermentations. So corn

31:33

and sugar cane, ethanol get incentives

31:36

in the United States that we don't receive.

31:38

So it's very hard to be competitive with something

31:41

that's getting an incentive. I

31:43

used the Tesla example. Remember Tesla

31:45

couldn't sell in New Jersey because it didn't have dealerships

31:48

and there were rules that actually block

31:50

new ideas, new marketing methods,

31:52

new sales method and that's the same

31:55

thing with what we do. I also

31:57

think there is this

31:59

natural skepticism of anything

32:02

new, and we always try to find

32:04

the problem with it. And so for the first

32:06

thirty years, twenty years, you've got to deal

32:08

with people telling you what you're doing is

32:10

wrong, and nobody ever says, Okay,

32:14

what you're doing may not work,

32:16

but that's okay because what we're doing

32:18

isn't working and so we need

32:21

to replace it. And so to

32:23

me, what slows us

32:25

down is people asking the wrong

32:28

questions. And I always

32:30

say, this is a

32:32

sector where we need allies. We

32:35

need people saying they're

32:38

going to get there. You need to push

32:40

them along and to help them along. And

32:42

this is what we're going to do to help these

32:44

industries grow. Rather

32:47

than not cost

32:49

effective, not the same profit,

32:52

not a good idea, I mean that negativism

32:56

is draining.

32:59

Thank you for going down the road of the sad

33:01

story. Oh, let's talk about the happy

33:04

story now, Like, tell me the

33:06

happy story. What's what's the happy story of the next

33:09

ten years.

33:10

Well, the happy story is very simple. We

33:13

have shown that you can take

33:15

every type of waste carbon that's already

33:17

above ground and make the products you use every

33:19

day sustainable aviation

33:21

fuel. We decarbonized steel

33:24

mills at the same time that we decarbonize

33:26

aviation, right, And you can poo poo

33:28

that all you want, but the fact is we've done it. We've

33:30

shown it. It works. And nobody

33:32

can tell me that fresh fossil carbon

33:34

is the future, and I can tell you,

33:37

let's just keep that carbon in the ground. So what

33:39

do the next ten years look like for us?

33:41

We're going to keep showing you that We're going to show

33:43

you that food, fuel and chemicals

33:46

can all be made from waste

33:48

carbon that's above ground.

33:50

And specifically, like, what

33:52

are the sort of big, big projects

33:55

in the kind of short to medium term for you?

33:58

Well, I think some of our big projects.

34:00

First of all, we've got to scale sustainable

34:03

aviation fuel, and so showing

34:06

our first plant and its economics

34:08

is going to enable a bunch of other plants

34:11

to get built. The other

34:13

thing I want to show is integration

34:16

more and more to reduce costs.

34:19

What you don't want is a unit

34:21

that makes ethanol and a unit

34:23

that makes aviation fuel, you

34:27

know, next to each other and not integrated,

34:29

or a unit that makes hydrogen that we

34:32

need to convert CO two being

34:34

a separate standalone. The more

34:36

we integrate, the cheaper things get

34:39

right. And so to me, as

34:41

we make our technology cheaper, I want to also

34:43

show that integration with others

34:46

is cheaper and cheaper, and that's where your economies

34:48

come in. And the final

34:50

thing I want to do is just really show

34:53

that biology needs to be thought

34:55

of differently. We you know,

34:57

petroleum is densest liquid known to man.

35:00

That's why we've grown these massive, centralized

35:02

refineries. What biology

35:04

can do is use

35:07

local resources, enabl a country

35:09

to use its local feedstocks and

35:13

be able to make selectively

35:15

the product it wants. So

35:17

do you want to make aviation fuel great?

35:20

Do you want to make polyester great?

35:23

And we want to do this and

35:26

leverage the power of biology to

35:28

enable economies to grow while

35:33

their population grows, because

35:35

the biggest concern I have is if

35:37

you're developing economy and you're watching

35:39

your population grow, every

35:42

time they buy something, a dollar goes out

35:44

of the country, so somebody else

35:46

gets paid for the goods. I

35:48

want people to be able to grow and grow their economies

35:51

and grow the jobs and grow everything at the same time.

35:53

And I think biology, with its

35:55

ability to be distributed and local

35:59

enables that, and frankly,

36:02

I don't think anything else does. And I

36:04

want to show that over the next five to ten years.

36:09

We'll be back in a minute with the lightning round. I

36:22

want to finish with

36:24

a lightning round oh uh

36:27

Oh. Your dad,

36:29

I have read, was an airline mechanic. Yeah,

36:31

and I'm curious how his work influenced

36:34

you.

36:36

He taught me how to fix things and to want

36:38

to fix things, and to care about aviation.

36:43

What was something you fixed with your dad?

36:46

Oh? Everything. I crawled around planes, although

36:48

I never fixed anything. I just crawled around

36:50

with him on planes and cars and things.

36:53

Yeah, that's cool.

36:56

What's one thing I should do if I visit Columbia?

36:59

Oh, my gosh, eat the food.

37:02

Yeah, the food is amazing.

37:05

What's one thing I should eat?

37:07

My favorite petic I don't

37:09

know what are That's

37:12

some plantains

37:15

that are not ripe, so they're

37:17

green, and you sqush them

37:19

and you fry them and you squish them again

37:21

and you put salt on them. It's kind of like the French

37:24

fries of Barankilla, which is where I

37:26

grew up.

37:27

I understand that you went to the Paris Olympics.

37:30

Oh, and you know, obviously

37:32

you work a lot with microbes, and so I'm

37:34

curious. Would you swim in the sun?

37:37

Ah?

37:39

I no.

37:45

Tell me about the first greyhound that

37:47

you rescued.

37:50

We rescued

37:52

two dogs, two greyhounds that had

37:55

badly broken their legs and

37:58

they had been repaired

38:00

by an agency, and then we

38:03

adopted them.

38:05

I learned that thirty percent

38:08

of greyhounds wash

38:10

out because they've broken something or have been injured.

38:13

It's a very sad, sad, sad thing,

38:16

and they are amazing dogs, amazing.

38:23

Jennifer Holmgren is the CEO of

38:25

Lanz Tech. Today's

38:27

show was produced by Gabriel Hunter Chang.

38:30

It was edited by Lyddy Jean Kott

38:32

and engineered by Sarah Bruguer. You

38:34

can email us at problem at Pushkin

38:37

dot fm. I'm Jacob Goldstein

38:39

and we'll be back next week with another episode

38:41

of What's Your Problem

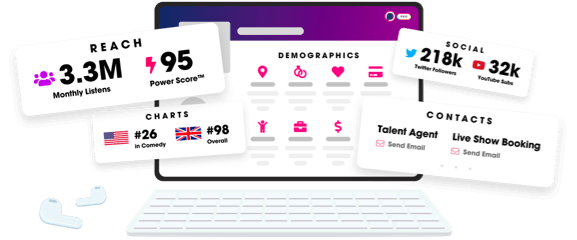

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us